On Deborah Stratman

Posted by | Ziva Schatz | Posted on | April 13, 2016

This week I am excited to welcome undergraduate Connor Crable to write for us! Crable sharply discusses Deborah Stratman’s newest film, The Illinois Parables, which deals with a series of histories that have been buried over time.

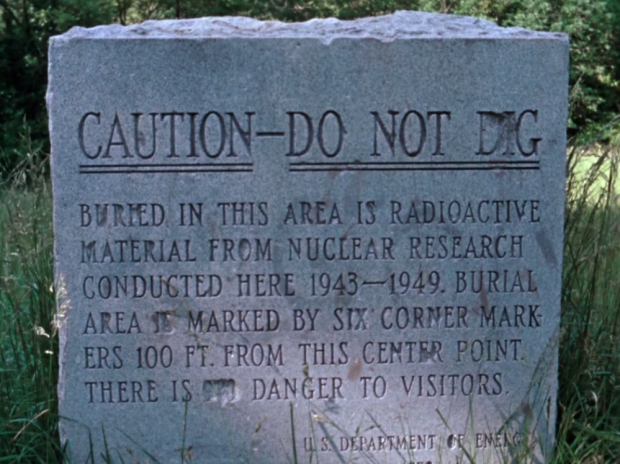

In just short of an hour, Deborah Stratman’s newest film, The Illinois Parables, ushers viewers through a series of histories that for various reasons have been buried. Michael Pattinson of rogerebert.com says the film “accelerates through fourteen centuries with maximalist abandon”. The events of the film begin in 600 CE and about fifty-five minutes later we have arrived in 1985. From the dispossession of Native American land, the exile and murder of Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, the dispelling of the French Icarian population, a set of mysterious fires rumored to be the result of the supernatural powers of a teenage girl, to the infamous murder of Black Panther leader, Fred Hampton, by the FBI and Chicago Police Department.

What all of the histories referenced in the film have in common is that they are all subaltern. These are histories of the dispossessed, extra-human forces, irrational events; in short, histories that resist historicization. Stratman approaches the complexities and mysteries of these stories through her use of sound. Across a long and varied practice, sound is a power that Stratman has consistently explored. This film is, to say the least, a unique sonic experience. Voice-overs are never accompanied by their talking bodies; instead, they speak over an enormous variety of archival footage, reenactments, and footage of signs and dioramas, diagrams and photographs. Music, often religious (a Bach oratorio, a Renaissance motet, and an astonishingly beautiful choral setting of the Credo by Estonian sacred music composer, Arvo Pärt, to name a few) burst forward from frequent silence. It is by some strange quality of the sound that the histories presented in the film feel so present, like they are unfolding again in the present in their own terms.

Stratman says this of the film, “The Parables consider what might constitute liturgical form”. We see such consideration in several of the narratives when politics take on a religious air. Parable 10 presents the assassination of the Black Panther’s could-have-been ‘messiah’ (in the words of the FBI), Fred Hampton. But The Illinois Parable’s relation to liturgical form is inherent in the structure of the film itself. The sound of the film often takes up the liturgical, at times feeling like prayer, sermon, or scripture. The brilliant power of liturgical form is this; it dissolves temporal and spatial distances, it brings the listener close. Maybe the first scenes of the movie illuminate this power best: A Native American man, Ravenwolf, describes the ritual of playing music on the tumuli. To Ravenwolf the songs he plays facilitate the process of receiving the gifts of the ancestors decomposing just below his feet. His songs open him up to learn from the past. It is that bit of wisdom that organizes The Illinois Parables. The film resurrects the voices and histories of those who were most likely excluded from your recent architectural boat tour, the bodies and forces that were meant to stay buried.

In a state notoriously flat, it is fitting that the mound would be the metaphor for what linear history tries to hide. All the histories in the film seem to rotate around this object. We see ancient Native American burial mounds. Mounds appear as bunkers and as safeguards against nuclear reactions. Mounds are flattened by tornado and fire. The morphing permutations of the mound are often accompanied by a bell (itself mound-shaped), which chimes forth quiet like and shakes the body awake like a well-struck prayer bell at the end of Savasana. Thus the sound of the film takes on a duel quality—as it resurrects the past; it also anchors the viewer to the immediate present. As an Illinois resident I can’t help but take the piece as more than just an example of how the filmic form presents solutions to the problems of telling subaltern history, because these are my histories now.

Connor Crable recently finished his undergraduate degree at SAIC with a BFA in Fall 2015.

Tags: 2016 > Chicago > Connor Crable > Deborah Stratman > Experimental Documentary > Political > SAIC Alumni