On Hyphen-Labs

Posted by | Paris Jomadiao | Posted on | March 29, 2017

This week, we are thrilled to present NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, the latest project by Hyphen-Labs, an international collective of women artists, designers, engineers, game-builders, and writers known for works that merge art, technology, and science.

In this interview with SAIC graduate student Mev Luna, the collective shares their thoughts on Afrofuturism, virtual reality, ritual, and other concepts related to their project and overall practice.

Mev Luna: Your latest project is titled, NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism. Afrofuturism is a term that is heralded in our contemporary moment, but can be traced all the way back to the 1970s, the root with Sun Ra’s film Space is the Place (1974). There are a lot of current manifestations of Afrofuturism in art, including the work of sound, video and installation artist Kamau Patton, who’s faculty here at SAIC; UK based conceptual artist Sonya Dyer and her collaborative project And Beyond Institute for Future Research; and the work of artist Otobong Nkanga, as discussed by scholar Denise Ferreira deSilva in e-flux journal.

How do you trace your lineage within Afrofuturism? And what aspects of the aesthetic are you drawn to?

Hyphen-Labs: We contextualize this project within the lineage of Black women’s literature, especially poetry and magical realism, Black art history and philosophy, and non-colonial scientific exploration. The themes, symbolism, language, and coded messages draw most heavily from Mother Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler, Tananarive Due, Colson Whitehead, Ralph Ellison, Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes. From an artistic perspective Arthur Jafa and Chris Ofili were informative to our work, as well as emerging artists we encountered on Instagram. So not specifically Afrofuturism as it manifests as a categorical and theoretical framework but people of color creating work that places us firmly within the context of futurity while subverting the white “validating” gaze. The idea of performing research in public spaces also resonates with the projects so thank you for the introduction to deSilva’s work.

ML: I’ve been thinking a lot about future and how it has been invoked in discourse around the marginal body, both in Afrofuturism–as claiming a black future to be called into a present in which black lives are precarious, and Black Lives Matter has been an important invocation–and in queer theory.

Similarly, in the opening of his book, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009, NYU Press), the late José Esteban Muñoz wrote that “The future is queerness’s domain. Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present. The here and now is a prison house. We must strive, in the face of the here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality, to think and feel a then and there.”

So I am curious, what does future mean to you? And what does it’s invocation do for us in the present–when so many marginalized people in serious state of precarity, and #nofutureness?

HL: We think of the future more in the realm of quantum physics. The future moves along a continuum of infinite possibilities and because of this, speculations about the future most often tend to reflect the dominant narratives of the current society positing the ideas. In quantum theory, looking at something changes its state thus re-rendering it. We’re looking at conversations being had about the future–especially in the digital landscape–and wondering where are the folks of color are. Speculative design is highlighting driverless cars, but we have yet to see a case study featuring a black or brown perspective. We have artificial intelligence reflecting the bias of the developers programming them, and it’s mostly not people of color so what you have is the erasure of histories and mis-categorization of black and brown bodies.

The problem is the future is rarely rendered by communities of color at the level of infrastructure and implementation. Where are the black and brown architects, engineers, programmers, mathematicians, quantum theorists, aeronautical engineers, chemists, roboticist, speculative biologists, neuroscientists, immunologists etc talking about the future on a global platform? Nope, it’s Elon Musk, Ray Kurzweil, Palmer Lucky, Mark Zuckerberg etc so current futurity is just repeating the past and present. The possibility of us starting from square one in the struggle for social justice is real unless we’re demanding our “spot at the table and bringing a chair” with us.

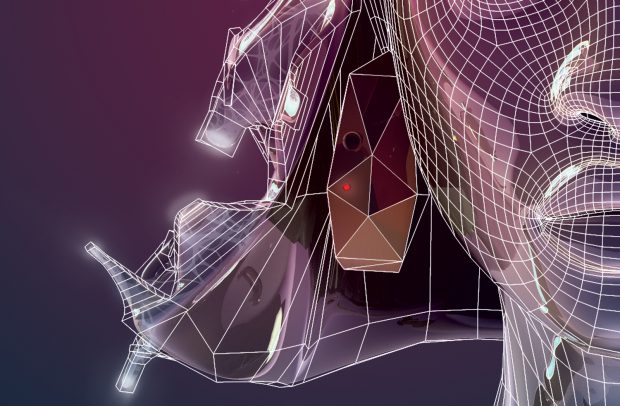

ML: Muñoz’s use of the word rendering reality makes me think about the medium of 3D rendering, which is also the medium of NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism. The virtual reality and augmented reality artist Claudia Hart situates 3D rendering as a combination of photography and sculpture. The interface of the software, be it Maya or other softwares, is a liminal space between the body and the screen. It’s post photography–and considering the vast ability to download 3D models from the internet or to scan ANYTHING and import it into 3D space–it is also a very postmodern medium.

Where did the collective’s interest emerge in working in this medium? And what does 3D rendering allow for in your project that other mediums do not?

HL: We chose the 3D medium because it is what we know and it is a space that evolves very rapidly. Trained as architects and engineers, our designs are constrained by this world’s physical systems, existing infrastructures, and material properties. In 3D, theses constraints drop away and we are able to express alternative pasts, presents and futures.

ML: 3D renderings are used more and more in commercial design, and given that Hyphen-Labs is a design firm as well as artistic endeavor, are you interested in this medium because of the aesthetic slickness it offers which is so readily found in contemporary design?

HL: Yes. As architects and engineers, 3D modeling, prototyping and digital fabrication have always been part of our work experience and we use 3D rendering to prototype what ifs… VR is an interesting medium because it fits the story we want to tell. Allowing audience to be enveloped in the materiality of our world and walk away having experienced many “feelings”.

ML: It seems as though the Beauty Salon is both a design implementation and a ritual. Not only a way to address the contentious issue of how the mainstream treats black hair, from Solange’s Don’t Touch My Hair (2016) to Phoebe Robinson’s book You Can’t Touch My Hair (2016, Penguin Random House), but also the black ritual of hair braiding. Do you see this work as ritual?

HL: This work is ritual at its core. We hear from black women who have done the experience that it felt familiar and safe. In this time where the black body is endangered, where black and brown women are being abducted a few miles from our nation’s capital and no one is talking about it, we wanted to build a space of ritual, self-realization, and reflection. Black hair holds our ase and our philosophy.

Tags: 3D > Ashley Baccus-Clark > Black Cinema House > Carmen Aguilar y Wedge > Ece Tankal > Hyphen-Labs > interactive > Interdisciplinary > Mev Luna > NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism > Virtual Reality