On Ming Wong

Posted by | Ziva Schatz | Posted on | November 4, 2015

This week we are excerpting Travis Jeppesen‘s Art in America interview with Ming Wong! To read the full interview see the “MORE” link at the end.

TRAVIS JEPPESEN: Petra von Kant, Gustav von Aschenbach, Jake Gittes, Evelyn Mulwray: These cinematic heroes and heroines have little in common except for having all been re-depicted by the Singaporean artist Ming Wong, who takes what the writer Kathy Acker dubbed “pla(y)giarism” to new levels of hilarity and provocation in his videos. Usually playing all the roles, male and female, Wong performs a “yellowing” of the Western cinematic canon that is as much a critical tool as it is an excuse for dressing up and acting out.

My first encounter with Wong’s work took place in 2010 at a group exhibition in Berlin that featured Angst Essen (Eat Fear), 2008, his hysterical and moving remake of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 film Angst essen Seele auf (known in English as Ali: Fear Eats the Soul). Shot ironically in the melodramatic style of Hollywood director Douglas Sirk, Fassbinder’s film depicts the courtship and eventual marriage of an aging German woman and a young Arab guest worker. In Wong’s version the artist plays both roles—and all the others in the film—with straight-faced solemnity and faithfulness to the original script in a 27-minute transduction.

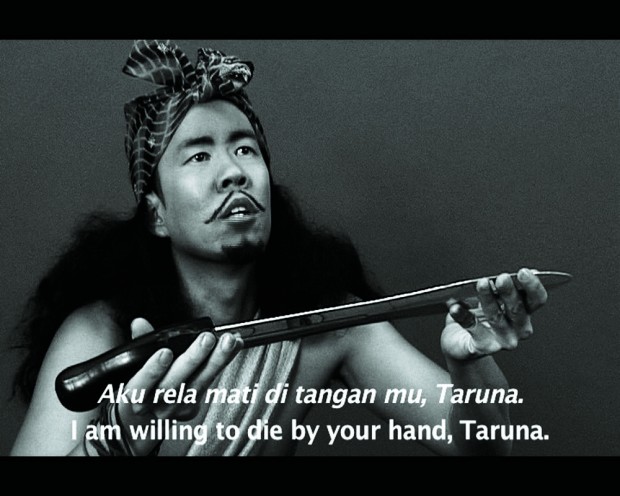

Ming Wong: Four Malay Stories, 2005, four-channel video installation. All images courtesy Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou, and carlier|gebauer, Berlin.

Of course, a disconnect emerges between the language being spoken—rife with the racist epithets and humiliations regularly directed toward Arab guest workers in Germany in the 1970s—and Wong’s inclusion of himself, an East Asian, in a scenario in which he is totally other. Non-German, non-black, non-white, non-Arab: the invisible man is suddenly reflected everywhere.

Before reading Wong’s work as a theater of absurdity, which in many ways it is, credit must first be given to what is ultimately the artist’s most disruptive gesture: through what he calls “impostoring,” his insertion of people traditionally excluded from cinematic representation into cinema’s traditional tropes, he endows those devices with new and often unsettling meanings.

Amid a hectic traveling schedule that frequently has the 42-year-old artist jetting between Los Angeles, Europe and East Asia, Wong met with me in his Berlin studio this past June, as he was making final preparations for a major solo exhibition at Shiseido Gallery in Tokyo (July 6-Sept. 22). His studio is situated in the predominately Turkish neighborhood of Kreuzberg, which initially inspired him to turn his attention to Fassbinder. Since I had just returned from the Venice Biennale, our conversation began with a discussion of Wong’s project for the Singapore Pavilion in 2009.

TRAVIS JEPPESEN: Tell me about the Life of Imitation project.

MING WONG: Life of Imitation was about Singapore’s cinematic heritage. Singapore was really the capital of filmmaking in Southeast Asia during the ’50s and ’60s. This unique chapter was started by Chinese producers, who owned the movie theaters in the early 20th century. They started making movies for their region, which meant Malay language movies (for Malaysia and Indonesia). They went to India to invite directors and cameramen to live and work in Singapore. Then you had Malay and Indonesian performers. So there was this situation with everybody trying to negotiate their way around each other and make cinema. You can imagine that they’d speak some sort of English mixed with other languages. The crew would probably speak in some Chinese dialects, so there was a cultural milieu that was very dynamic. Everyone would watch these movies when they were screened in Singapore. As a child, I remember seeing reruns on television. In those early days, in the single-screen cinema halls, you’d just watch everything, whatever language it was in.

Tags: 2015 > Germany > Humor > Ming Wong > Performance > Political > Reenactment > Retrospective > Singapore > Travis Jeppesen