On Stan VanDerBeek

Posted by | Nicky Ni | Posted on | September 12, 2018

Conversations at the Edge opens its Fall 2018 season this week with a program surveying the career of pioneering American media artist Stan VanDerBeek. Focusing on VanDerBeek’s computer graphics films, this program also coincides with an exhibition of the artist’s work at DOCUMENT. For this post, we welcome SAIC student Sophie Jenkins (Dual MA, 2020), who has worked on the exhibition, to reflect on the history behind VanDerBeek’s most well-known computer-generated films Poemfields.

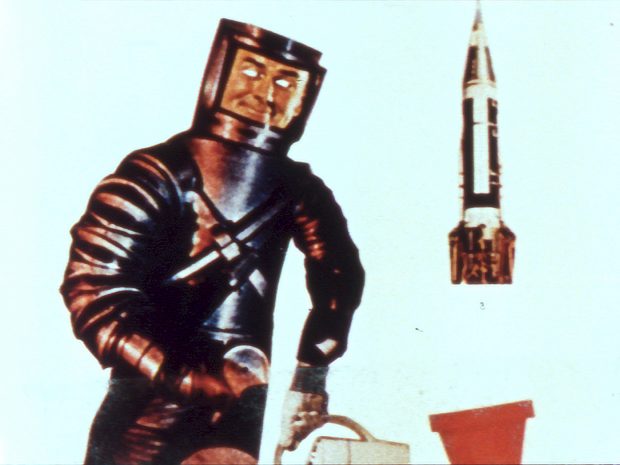

Stan VanDerBeek, still from Poemfield No. 7, 1967-68. Image courtesy DOCUMENT/The Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

the artist-filmmaker today

is caught between the age of realism and surrealism

and is off on the journey beyond reality

— Stan VanDerBeek, “Interview: Chapter One,” Film Culture 25 (Winter 1964-65): 21.

A pioneer in experimental filmmaking and computer animation, Stan VanDerBeek began his artistic career as a painter. During his early days as a student at Black Mountain College in Asheville, NC, VanDerBeek was greatly influenced by the practices and writings of poet M.C. Richards and composer John Cage. Their multidisciplinary work especially contributed to VanDerBeek’s development as a multimedia artist and his interest in developing what Gloria Sutton calls an “image-based poetry language.” In the 1950s and early 60s, VanDerBeek moved on from painting to produce zany collage films using stop-motion animation with altered clippings from magazines and newspapers. Astral Man (1958) and Science Friction (1959), both included in the program, are examples of these early films that helped establish VanDerBeek as a significant filmmaker in new-avant-garde American cinema.

In the mid-1960s, VanDerBeek’s growing interest in what would be defined by Gene Youngblood as “Expanded Cinema” led him to build a “Movie-Drome” in Stony Point, New York, as a laboratory for audiovisual performances that unconventionally juxtaposed images and texts. He meant for this experimental theater to function as a model for a new visual communications system and envisioned the immersive experience as a locus for the exchange of art and ideas. VanDerBeek’s research into developing visual languages as ways of communication also led him to seek out expertise from individuals pioneering in the fields of film technology, digital media, and computers. In 1964, VanDerBeek began collaborating with computer scientist Ken Knowlton at AT&T’s Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey. Their joint project was facilitated by the artist/engineer collective E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), co-founded by artist Robert Rauschenberg and Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver in 1966. Trained as a physicist, Knowlton had worked in the Labs’ Techniques Research Department since 1962 where he developed many innovative computer graphic programming languages, including BEFLIX (short for “Bell Labs Flicks”). Knowlton conceived BEFLIX in 1963. From 1966-69, VanDerBeek and Knowlton used BEFLIX with an IBM 7094 computer and punch cards to to construct a series of eight computer-generated animated films titled Poemfields.

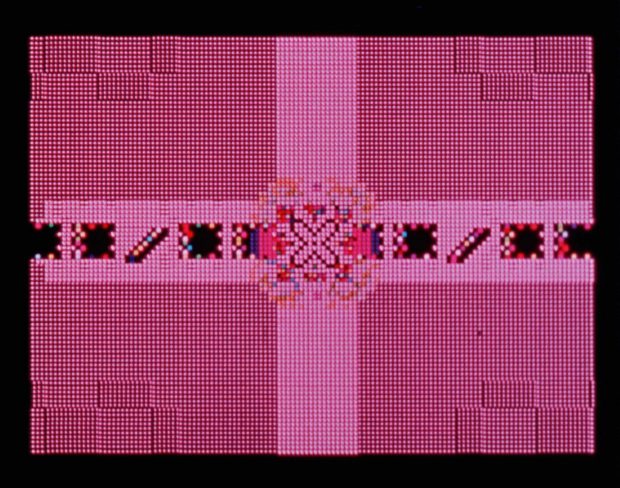

Still image from Stan VanDerBeek: The Computer Generation (1972), a TV short directed by John Musilli and Stan Vanderbeek.

Multilayered moving images of abstracted colors, visuals, texts, and sounds, VanDerBeek’s Poemfields are empowered by the computer’s ability to generate text on a screen. Introduced to him by Knowlton, this was a novel and enlightening technique for VanDerBeek and became critical to his cinematic output. Evidence of VanDerBeek’s early interest in manipulating the visuals of language, each Poemfields film combines the artist’s own poetry with a range of digital illustrations. VanDerBeek originally created the films in black-and-white, with color added later by filmmakers Robert Brown and Frank Olvey. He worked with John Cage and musician Paul Motian to develop soundtracks. Four films from the series (Poemfield Nos. 1, 2, 5, and 7) are part of the CATE program.

Stan VanDerBeek, still from Poemfield No. 7, 1967-68. Image courtesy DOCUMENT/The Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

Rather than employing on a camera to traditionally capture images, VanDerBeek made use of the computer as “an abstract notation system for making movies” and saw film as raw data for “image storage and retrieval systems.” VanDerBeek’s multisensory approach to art-making and movie-making aligned with those neo-avant-garde strategies that challenged the primacy of the canvas and the predetermined trajectory of an artistic medium. A survey of VanDerBeek’s films highlights VanDerBeek’s contribution to the plurality of artistic and cinematic practices that has come to define contemporary filmmaking.

For additional perspectives on VanDerBeek’s significance as an artist and filmmaker, visit DOCUMENT for the gallery’s exhibition of VanDerBeek’s multimedia work. The exhibition, Poemfield, will present a 16mm film installation of Poemfield No. 7 (1967-68), a digital projection of Symmetricks (1972), and a selection of framed works on paper (1973-83). The exhibition will open on Friday, September 14.

Sophie Jenkins is in her second year of pursuing a Dual MA in Art History and Arts Administration and Policy at SAIC. During summer 2018 she worked as an intern at DOCUMENT and gathered research in preparation for the gallery’s Stan VanDerBeek exhibition.

Tags: 2018 > Computer Graphics > Digital Media > Document Gallery > Experimental Film > Stan VanDerBeek