Naming the archive

Friday, July 14th, 2017 » By James Connolly » See more posts from Blogging the Archive, Staff Projects

By Gabe Wilson and Lara Schoorl

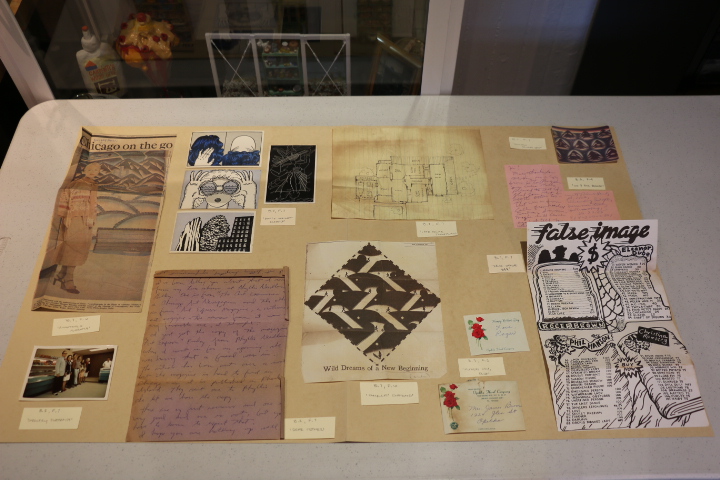

Sometimes it is nice to look without a set purpose. Creating an archive for the first time started like that. We were given three boxes, and then a fourth, with papers and ephemera related to Roger Brown and his family. These documents would become part of the archive of the Roger Brown Study Collection, but first everything had to be sorted: letters, clippings, photos, and ephemera, saved over more than three decades by Greg Brown (Roger’s brother) and his parents. Every piece, when understood in the light of a network of familial, creative, and documentary correspondence, is a testament to the Brown family’s desire to preserve the physical evidence, beyond his works, of Roger’s creative life.

It is strange, the work of archiving, particularly in a house museum. Archiving is an inherently idiosyncratic practice and, perhaps not surprisingly, a deeply intimate experience. In sifting, ordering, and cataloguing the ephemeral traces of a space, place, or person, the wonder of the seemingly mundane quickly captivates and complicates our understanding of history in its most discreet sense.

A selection of clippings, letters, photographs, drawings, and exhibition ephemera from the new archival documents shared with the RBSC by Greg Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

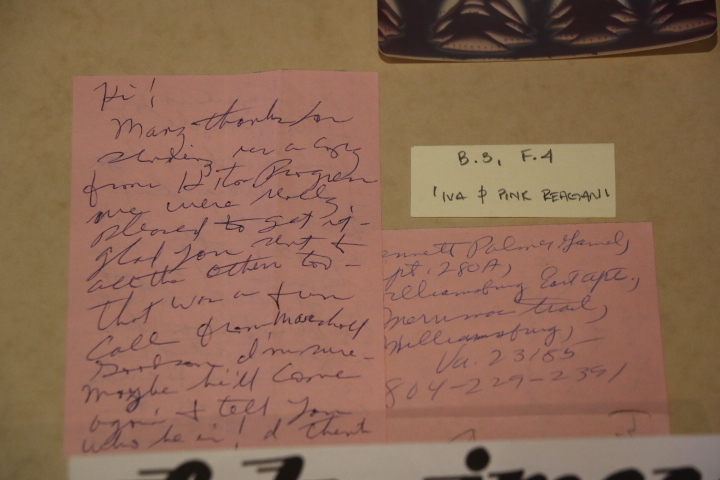

When given the task to sort these documents, what does one sort by? This was perhaps the first question to emerge at the outset of this project. Do we sort per person? Per type of document? Do we sort by both? And do we document as we sort, or sort everything first? And when documenting what language does one use? Working on this archive as a team of three people, we had to ensure that there was consistency across all of our contributions. This in a way seems restrictive and bureaucratic, but it also gave us freedom to discover a language of our own. Pink paper was documented as “pink paper;” the color became important. Similarly, large envelopes were named “manila envelopes,” for their color as well and their shape, and regular envelopes became “envelope addressed to.” If the stamps were interesting stamps would be described. Everything that made a document special—that indicated it was that document instead of a similar or the same document but saved by another person—had to be described in such a way that we were able to distinguish two or more similar objects.

Our language became visual and objective, yet remained very particular to our individual perceptions of the materials upon first encountering them. Additionally, questions arose as to what purpose duplicates served. Does it indeed make a difference if there are two of the same documents, but collected by different people? Is it ok to toss a newspaper clipping from 1982? If one clipping contained writing in the margins, it became more valuable than its duplicate, because it was touched more, physically, by one of the lives that is part of this archive. And, should we keep envelopes? Many have Roger Brown’s handwriting on them? These considerations highlighted larger questions around the power of remnant and its ability to express history.

Pink paper notes from Aunt Iva to Elizabeth Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

Pink paper notes from Aunt Iva to Elizabeth Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

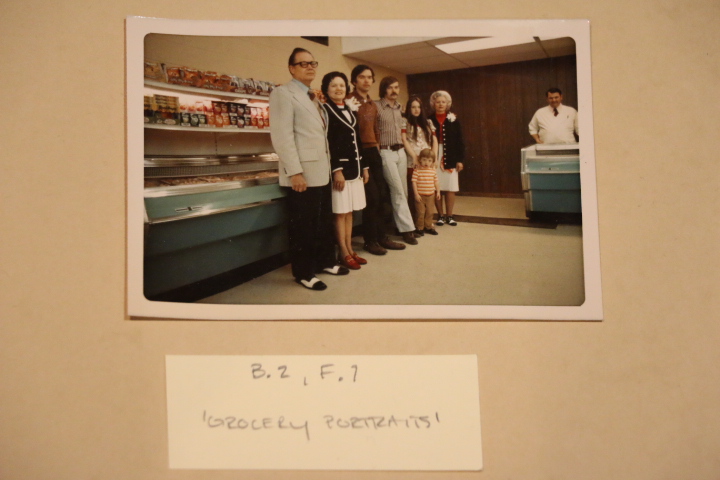

A photograph of the Browns in their family grocery store in Opelika, Alabama. Left to right: James Brown, Sr., Elizabeth Brown, Roger Brown, Greg Brown (others unknown)

A photograph of the Browns in their family grocery store in Opelika, Alabama. Left to right: James Brown, Sr., Elizabeth Brown, Roger Brown, Greg Brown (others unknown)

In many ways, cataloguing the contents of what we called “The Greg Brown Boxes” emerged as a cartographic act. In mapping these materials, orientation was often as important as location. Understanding what a document was necessitated an exploration of how a text or image was situated in relation to a greater material landscape. The import of a photograph of Brown and his family in the their hometown grocery business emerged through a series of letters between Roger, Greg, and their father that illustrated the complicated, sometimes contentious, lifecycle of a family enterprise that was integral to their conception of familial history and whose legacy held different implications for each member involved. Place, particularly homeplace, speaks to a drive in Brown’s work to site his pictorial narratives within a deeply personal landscape.

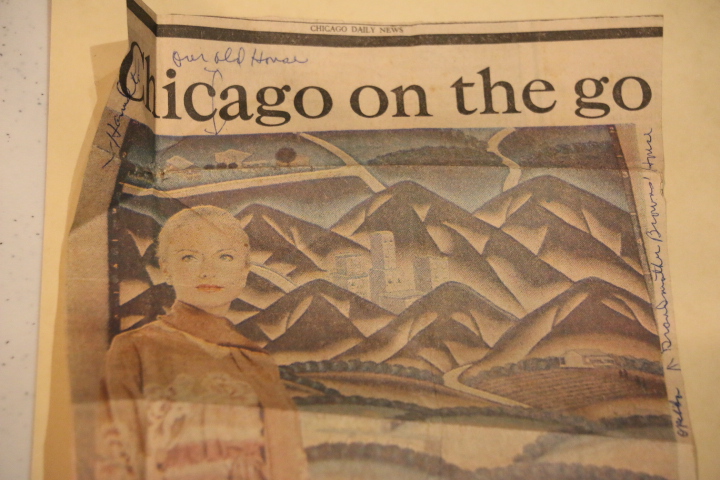

Though occasionally obtuse in his own idiosyncratic methods, Brown often readily addressed specificity in his work through titles and the direct incorporation of text within image. One of his more notable early works, Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama (Mammy’s Door) (1974), speaks directly to a compulsion towards reenacting the known world as something intimately and individually experienced. In a Chicago Daily News article published in the Fall of 1977, Roger’s homage to genealogical history and sentimental landscape became a backdrop for the wife of Chicago’s then mayor and a discussion of an emerging fashion industry in the Windy City. And yet, despite the preservation of many journalistic and critical texts specifically concerned with Roger’s work and exhibition life by the Brown family, this faded society write-up resonates, for me, most eloquently—and in Roger’s own hand. “Our old house”, “Opelika”, “Hamilton”, “Grandmother Brown’s home”; Roger activates the allegorical landscape of his painting with the reality of a deeply intimate history. He translates, for the recipient of this clipping, the very real stakes he took up when portraying home.

Clipping of “Chicago on the Go” by Patricia Shelton from October 4, 1977 edition of Chicago Daily News. Annotations attributed to Roger Brown.

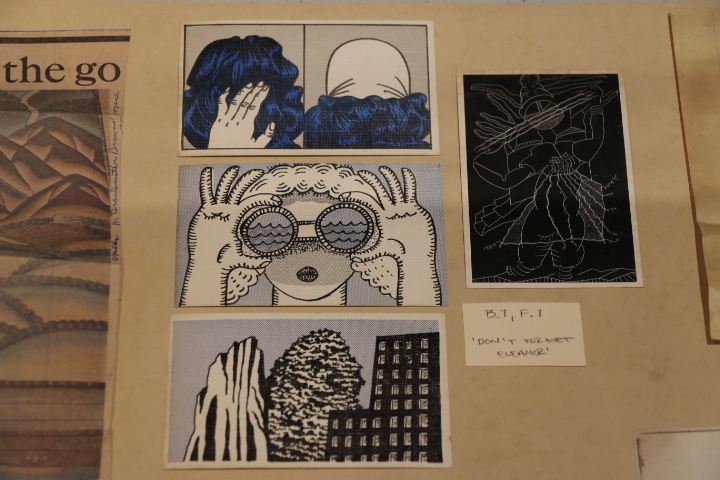

We were looking at lives, and those lives became part of our own lives. Would I have recognized and remembered the tattoos on a guy’s shoulders if I had not fallen in love with Christina Ramberg’s postcard for the False Image exhibition? Or, when a few weeks ago I drove to Iowa City from Chicago with friends we passed a sign on the I-88 that read “Reagan’s Boyhood Home” I knew we were passing Dixon. I knew, because Aunt Iva (who had lived in Dixon) had kept and sent so many flyers that said “Help Preserve Reagan’s Boyhood Home,” because I had read a Chicago Sun-Times clippings from 1980 that proudly wrote about Reagan’s early life in Dixon.

In creating this archive we were given only the limits of the material of the archive. Within those borders three subjective beings started the archive with choosing the first document to be picked up and sorted. And thus, this project literally has formed through our hands. We looked, but were not looking for. We created in a way another life of/for this archive, which apart from its physical presence now also lives as a written and document that will be accessible to whomever comes across it and wants to come across it, and maybe becomes part of more lives.

Three promotional postcards for the exhibition False Image from 1968 at the Hyde Park Art Center. (Christina Ramberg, Phil Hanson, Roger Brown and Eleanor Dube)

Gabe Wilson and Lara Schoorl worked on this project as graduate student staff members at the Roger Brown Study Collection. Anna Lenz (MA Art Education ‘15) also worked with them on the project. The Roger Brown Study Collection Archive is open to researchers and the curious by appointment. rbsc@saic.edu

Lara Schoorl is a poet, curator and art historian from the Netherlands and lives in Los Angeles. She holds a BA and an MA, both in Art History from the University of Amsterdam, and is finishing her graduate degree in Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the publicity manager at The Green Lantern Press in Chicago, and works at the Museum of Jurassic Technology and Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles. Her recent writing can be found in The Conversant, The Huffington Post, Tique Art Paper, University of Arizona Poetry Center Blog, The Los Angeles Review of Book, and the anthology Sisternhood. She is a co-author of the end of may.

Lara Schoorl is a poet, curator and art historian from the Netherlands and lives in Los Angeles. She holds a BA and an MA, both in Art History from the University of Amsterdam, and is finishing her graduate degree in Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the publicity manager at The Green Lantern Press in Chicago, and works at the Museum of Jurassic Technology and Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles. Her recent writing can be found in The Conversant, The Huffington Post, Tique Art Paper, University of Arizona Poetry Center Blog, The Los Angeles Review of Book, and the anthology Sisternhood. She is a co-author of the end of may.